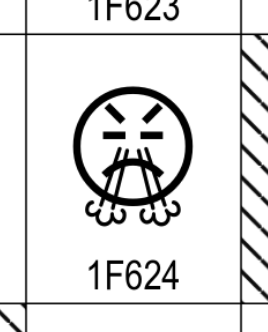

Whenever I see the 😤 face with steam from nose emoji on Discord, I give a little chuckle because the emoji is called :triumph:, even though the sender’s intention is anything but triumph. Discord, like most modern software, follows the Unicode standard, which assigns a unique “codepoint” number to every text character. The emoji was originally added into the Unicode in version 6.0 along with the first batch of Unicode emoji and was named “FACE WITH LOOK OF TRIUMPH.” Although the technical Unicode names never change for backwards-compatibility, Unicode’s Common Locale Data Repository, a dataset that reccommends translations for emoji names (among other things), primarily lists the emoji as “face with steam from nose.” The latest versions of the Unicode standard (13.0 at the time of this writing) now have a special note saying “indicates triumph, not anger” after it became evident that an angry-looking face with hot steam coming from the nose looks more like anger than triumph. Where did the steam face come from and how did it make it into Unicode as “triumph”?

Japan

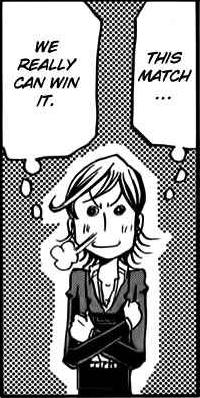

As always, the answer to weird emoji-related questions is Japan. Specifically, a face with steam coming from the nose is sometimes used to indicate someone triumphing or bragging in manga. Someone involved in adding emoji to Unicode (who I believe to be Katsuhiro Ogata, one of the emoji proposal authors) asked people to send in manga examples of the triumph emoji and the smirking emoji in this blog post (in Japanese). Though the examples recieved for the triumph emoji never made it to the Unicode Consortium (the smirking examples appeared in Rationale for Proposal of N3778), they did get posted to the blog. The originals are in Japanese and are viewable here and here. However, I’ve tracked down an English-translated version of one of them; Honey and Clover Vol.6 p.97:

There’s also another one not on their blog that I think fits even better, since he’s got a furrowed brow and not a huge, open smile. This one’s from Giant Killing Vol.12 Ch.109. Despite its name, the manga isn’t about killing gigantic humanoids but is instead about soccer.

Of course, representing triumph by having steam come out of your nose is practically unheard of for Westerners, so we might not understand “triumph” just by looking at the face. Ogata notes this as well:

It’s true that the most important part is that the face is facing upwards, the eyes are closed, and the nose is exhaling. Certainly, this is “triumphant pride.” However, since using the nose to represent “proud” is emphasized so greatly, I wonder whether or not people in the West who do not know manga expressions can understand it. The emphasis on your nose when you brag is unique to Japan, isn’t it? This is a subtle point.

Phone companies

Since emoji were invented by Japanese telephone companies for text in phones, naturally a lot of the early Unicode emoji are Japan-centric. For example, the 📛 name badge emoji for Western users looks less like a name badge and more like a flaming piece of tofu, but is in reality a tulip-shaped name badge worn by Japanese kindergarteners.

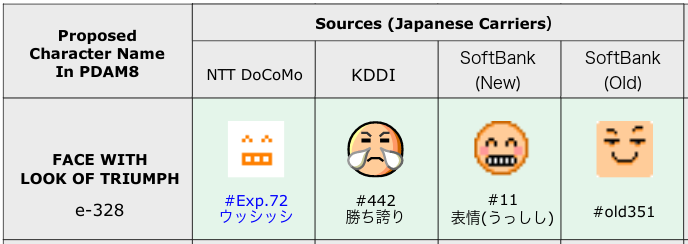

When Unicode considered including emoji into the Unicode Standard, it had to look at existing renditions of the emoji it wanted to include. They did this to map existing emoji that express the same thing to one emoji codepoint in Unicode, making it more compatible with multiple companies’ different sets of emoji. Unicode looked at four major telephone companies that used emoji: DoCoMo, KDDI, and SoftBank. For the triumph emoji, these companies had the following renditions:

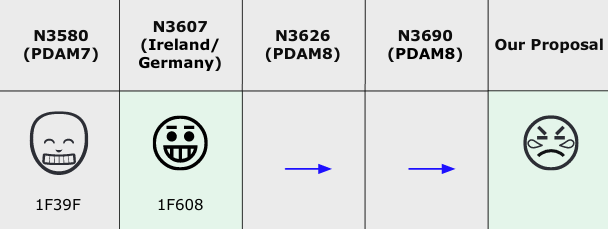

You’ll notice that KDDI’s rendition is the only pre-Unicode rendition that looks like the Unicode reference emoji. In fact, early proposals for the triumph emoji were smiling, which Western audiences might associate more with triumph. The smile was the first, shown in proposal N3580, and was carried on with a more round look in N3607 Towards an encoding of symbol characters used as emoji, which was written jointly by the Irish and German National Bodies and wherein they complained about anime on page 1.

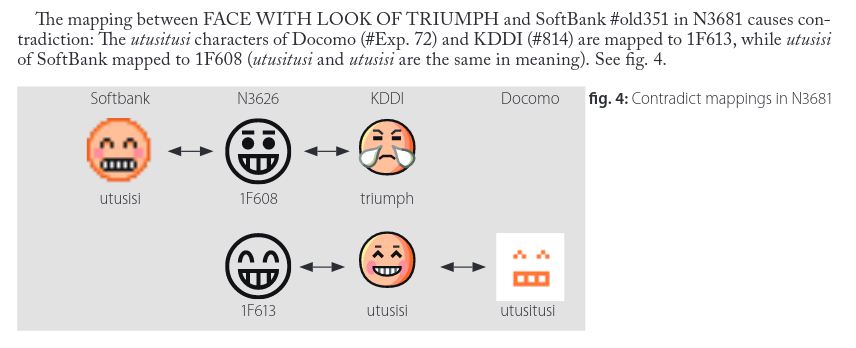

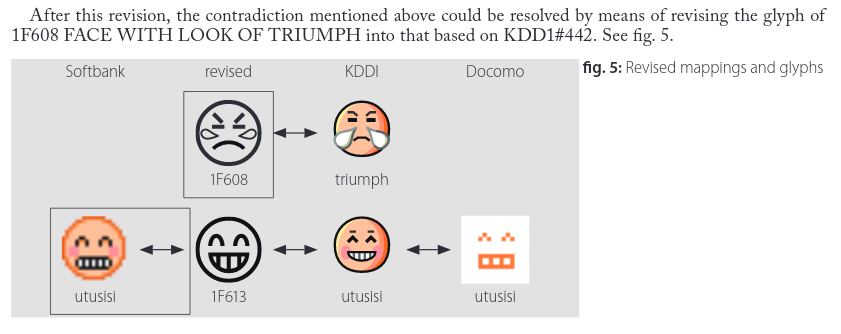

The Japanese delegation discovered a problem, however. DoCoMo’s emoji #Exp.72 ウッシッシ (utusitusi) was being mapped to the Unicode triumph emoji at codepoint 1F608, but SoftBank’s #11表情(うっしし) (utusisi) emoji was being mapped to Unicode’s happy face with grin emoji at 1F613. In addition, KDDI has an utusisi emoji separate from their triumph (勝ち誇り) emoji.

Since utusitusi and utusisi mean the same thing, it doesn’t make sense for them to map to different Unicode emoji. So the Japanese proposed that DoCoMo’s and SoftBank’s smiling emojis get mapped to Unicode’s happy face with grin emoji. The design of Unicode’s triumph emoji was then changed to look more like KDDI’s.

Where’s the upturned nose?

When we looked at Ogata’s blog post from earlier, he mentioned the upturned face and the emphatic expression of the nose. In the original Japanese, he writes that the nose indicates “鼻高々” (hanatakadaka). Idiomatically, it means “proudly” or “triumphantly,” but literally it means “nose very high.” So for many Japanese people, the feature of the upturned nose might create a strong association between the expression and the feeling of triumph. But from the static images of the KDDI emoji presented to Unicode, it doesn’t look like the nose is upturned at all! However, KDDI had animations for some emojis, with triumph being one of them. In the animated version, you clearly see the face turning upwards before the steam billows out from the nose.

According to a later blog post, Ogata apparently felt that something was off with the steaming nose Unicode emoji when he proposed it, but didn’t realize it was because of the lack of upturned nose until he saw all the manga examples people sent to him. By that time, it was too late since he already sent the proposal to the Japanese National Body to Unicode. So in the end, this is how we got our current emoji.

What does this mean?

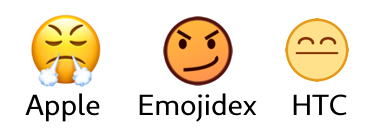

Unicode technically does not tell font designers how to style their emoji. Font vendors can and have deviated from Unicode’s reference art. HTC and Emojidex’s versions of the triumph emoji are completely different from Unicode’s, and have no steam at all. However, it’s worth noting that most vendors base their emoji designs off of Unicode’s art so the emoji remain recognizeable across platforms. (Sometimes this has disasterous consequences, like when Google misinterpreted the dots on the black-and-white version of the 💛 yellow heart emoji as hair and ended up making a hairy heart instead).

If font designers can choose to change their emoji art, why do most vendors choose to stick with the huffy steam face when it’s so often misinterpreted as anger? The problem is that every message already sent that relied on the existing emoji art will change in their perceived meaning. The underlying character encoding is still the same, so if you wrote “I can’t believe I lost the game! 😤” and suddenly the art changed to look triumphant, that would undermine the meaning of your text.

People hate it when you twist the meaning of their words, and emoji are no different. In 2016, Apple changed their 🍑 peach emoji art to look less like a butt, but it turns out as little as 7% of usages actually refer to the fruit, according to Emojipedia. The change caused a massive backlash, creating an uproar on Twitter and some sites saying that “Apple just ruined texting.” Apple quickly changed the art to meet the demand.

Semantic shift is natural

Just because the official Unicode name is “FACE WITH LOOK OF TRIUMPH” doesn’t mean the angry usage is wrong. Thousands of years before emoji were Chinese characters. They were originally pictures, so 口 means mouth because it looks like a mouth (^ 口 ^). After millenia of evolution, new characters were added, and the meanings of old ones changed. Once upon a time, 自 represented a nose. Since then, the original meaning shifted and came to mean “self.” The first person to use the character in the new modern sense of “self” wasn’t wrong, nor was anyone who used it to mean “nose.” It’s just that language changes, and words get imparted with new or different meanings. Emoji are no different. Emoji is language.